周靖轩 (Master Zhou) performs the applications.

Speed

Saturday, December 30, 2006

| [+/-] |

Pi Kua Quan (劈掛拳) |

The literal translation of Pi Kua Quan into English is "Axe Hitch Fist". Pi Kua Quan, a style of Traditional Chinese Kung Fu, originated in the same area of China as Baji Quan (Hebei Province in Northern China). The two styles are also closely related. Pi Kua Quan employs powerful long range palm strikes that can be executed with tremendous power. The source of Pi Kua Quan's power comes from its method of movement. The rotation of the entire body is what gives Pi Kua Quan its strength, similar to Baji Quan. Pi Kua Quan combines smooth hip movements to generate a flowing strike. Baji Quan, however, employs much shorter strikes. Power is generated from the combined rotating sweeping motions of the arms and properly balanced stance. A practitioner of Baji Quan would do well to learn Pi Kua Quan, and vice versa. The two styles share a common background and can provide a well balanced education for the traditional Kung Fu enthusiast.

Friday, December 29, 2006

| [+/-] |

Baji Quan Performance |

Performed by Damon Hwang (黃偉哲) on 2/02 in Taipei.

| [+/-] |

What is 八極拳? |

Known for its effective techniques and explosive power, Baji Quan is one of the best examples of traditional Wushu (Chinese Martial Arts). It can be literally defined as the "Eight Extremes Fist" or "Fist of the Eight Diagrams." This style finds its roots in the Meng Village of Cangzhou in the Hebei province of Northern China. While mainly practiced in Northern China, there are branches that can be found in the south as well. Baji Quan is a style that has a history going back hundreds of years. Used primarily for its martial aspects, Baji was implemented in the armies for its proven effectiveness during warfare . In modern times, Baji is implemented in the training of certain branches of the Taiwan police force. Requiring many low stances, Baji Quan develops the muscles of the legs and helps to refine rooting skills. From the outward appearances Baji Quan seems to be short and to the point. Internally, it's a different story altogether. Implementing shoulder and elbow strikes are a popular part of the Baji philosophy. Coupled with explosive engery powered by proper rooting and Fa Jin, tremendous damage can be inflicted if with a single strike. Baji Quan's motions of form involve a method of stomping which effectively sends a current of energy into the Earth. With the intention of being used not only as an attack but also as defense, Baji Quan's motions are indeed effective. Some branches of Baji Quan include Wu Style Baji Quan, Kai Men (Opening Gates) Baji Quan.

| [+/-] |

太祖長拳 Tai Zu Long Fist |

Performed in by 賴志垣 in Taiwan.

Northern Shaolin Long Fist.

| [+/-] |

Long Fist Power: Training the Complete Martial Artist & Complete Person |

By Adam Hsu

Misconceptions

Long fist is known for its proud and courageous spirit which clearly can be seen in its forms: the postures are dramatic and expansive; the movements are complex and elegant. They are very beautiful to watch. When performed by a high-level practitioner, an additional depth and power shine through. Unfortunately, these positive attributes have also helped foster some wrong ideas about this art.

There is a tremendous amount of valuable training buried within long fist's many forms. Of course nowadays it's well known that the old masters deliberately withheld important training and disguised real usage. Most students were given a form to learn, then another, and another, with no clue as to what they were really supposed to be practicing. Only a select few received the full training in secrecy. Without this understanding, there was no way to digest the true content of the training. It's no wonder people came to the conclusion that the more forms you learned, the higher your kung fu would be. Chasing forms is one of the reasons the level of contemporary martial arts is so low. Unhappily, practicing this way alone will make the road to mastery extremely difficult for anyone, no matter how talented.

There are several other important misconceptions people have about long fist. Many think that with its wide-open movements, it may be a good exercise but it lacks the mental training that Chinese martial arts are known for. Or it's purely an external style, shallow and solely physical. Others consider it just a pretty dance, filled with fancy movements that are beautiful to watch but useless in combat—if your real interest is martial arts, you'd be better off studying something else.

Nothing could be further from the truth!

Certainly long fist itself must share the blame for these misconceptions because it's possible the old masters held back too much of the art. It's so easy to look back in history and pass judgment on them but in actuality, no one today can really say what the correct dosage should have been. What we can say is that because of this practice, some of the art has been lost.

People may wonder whether long fist's generalized focus ends up diluting its own power and diffusing the fighting ability of its practitioners. Is it less intense and effective than styles with a specific focus? Not at all! But it's quite true that talented students of specialized styles can reach a high level in a shorter amount of time, compared to their long fist counterparts. In general, it is easier to achieve success by focusing on one or a few techniques than by working to make every technique equally good.

For this reason, dedicated and capable long fist students have quite often been known to lose matches to other stylists with less training. Needless to say, this has demoralized many a promising student and also supported the misconception that long fist can't be used to fight. When long fist students receive incomplete training, then all the criticisms about this style are true. But it shouldn't end up like this. With full and correct training, delivered within a systematized, efficient, modern program, students can follow the system step by step to reach the highest levels. When the real chang quan can be fully performed, when the practitioner has matured in his art, the actual fighting level is very high and deserves the utmost respect.

Ability and character

To fully understand the training you have to know the usage. And let me mention again, for security reasons, usage was hidden. The long fist family had a different attitude and approach to its students: the emphasis was on improving the student as a whole person, not just teaching how to punch and kick others. Over years of training, the sifu put his students through many covert tests of ability and character. Only when he had complete confidence in you, would he reveal the real heart of the art, teach the missing links that previously had been withheld in your training, and show you the usage. After all, in ancient times he and his entire family would be executed if you went off to commit crimes against the state.

Hidden usage

What does it really mean to say that the usage is hidden? How could you practice the cha quan form for years, know each movement so well you could perform it in your sleep, and not know its usage? Anyone can see that a punch is an attack. The circular sweep your other arm made before the punch is easily a block. This high strike you're about to deliver—your opponent better guard his nose! That forward kick—an attack to a target in front of you, and all of those circles your arms made as you were kicking, well they kind of protect your own face and besides, they look really beautiful. No big deal—you don't have to strain very hard to explain the usage.

But pay attention: very importantly, we all must understand that this interpretation is quite elementary. In long fist forms, usage that is obvious to the eye and easily interpreted is lower level. Long fist has very high usage; its movements contain much, much more.

When I was in high school, I myself began to study long fist. The training was often puzzling to me. Why did my teacher insist that my palms be held in a precise way when I was really practicing my kicks? And when I sparred with my classmates, the results were totally unpredictable and inconsistent. So I moved on to other styles that were more understandable and useful to me in winning my fights. It was only much later, as an adult with many years of hard training and martial arts exploration under my belt, that I realized long fist is not at all useless. Its techniques are very very high, and the strange demands made by its training suddenly made sense. Without them, it would be virtually impossible to attain the full potential of this art.

Fortunately, there is no longer any need to hold back information and techniques. What we know we can share with people comfortably, without guilt.

To this day, I still practice long fist. It is central to the training program in my schools. I continue to actively promote this style, sharing its true meaning and value with my fellow martial artists.

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

| [+/-] |

Northern Shaolin Longfist |

Northern Shaolin Longfist Performed in Taiwan by 蘇紀正

| [+/-] |

Long Fist Power: Training the Complete Martial Artist & Complete Person |

by Adam Hsu

Long a couple hundred Chinese martial art styles, it's a pretty safe bet to say that long fist (chang quan) is the largest style of them all. Now, if you count heads based only on the name "chang quan," you are likely to lose your bet. But as a matter of fact, as a matter of reality, long fist is truly the largest.

Some styles in this family are actually called "chang quan:" tai zhu chang quan (tai zhu long fist), jia men chang quan (Islamic style long fist), mei hua chang quan (mei flower long fist), and so forth. Others have totally different names, but still are long fist: for instance, mizong quan (lost track style) and even taiji quan (grand ultimate style). Yes, taiji quan is chang quan.

Long fist technique is rooted in ancient Chinese philosophy. Its theory emerged from China's traditional wisdom. Long fist fighting techniques, based upon this theory, evolved over centuries of trial and error: private bouts, skirmishes to defend family, employers, and villages, and the bloody battlefields of war.

Chinese martial arts has a huge number of impressive fighting styles. Some are quite unique, many are superb. What makes long fist stand out among them, what makes it unique is the balance and even development of its techniques and its versatility in fighting situations.

Does it emphasize arm or leg techniques? Long fist develops both.

How about long-range, midrange, or short-range fighting? Where is its strong point? Not a relevant question: long fist uses all of them.

Does it specialize in palm strikes? No, long fist uses fist, palm, elbow, shoulder, torso: everything and everywhere.

Which method of power-issuing does it employ? Long fist uses all possible ways.

Does long fist's fighting strategy call for initiating the first strike or waiting for the opponent to attack before responding? Long fist uses all different fighting strategies. And very importantly, the fighting plan must never be pre-designed.

Equal Opportunity Training

We might conclude, from looking at its theoretical-philosophical basis, all-inclusive range of fighting techniques, and flexible approach to handling situations, that a long fist training program—from its basic beginnings through the most advanced levels—has to be evenly composed and very well-balanced. And this is true. This is the fundamental personality of long fist.

All of them are excellent styles, and all have definite specializations.

Long fist, however, went to the opposite direction. You could say that long fist provides "equal opportunity" training for the entire human person. Its more generalized approach is quite comprehensive and develops the student's abilities in a more even manner. It prepares its practitioners to face any situation with an arsenal of different techniques at their disposal.

Looking at it from this point of view, we can see how many kung fu styles grew out of long fist. Long fist is like a mother to northern Chinese martial art styles. All of her children carry characteristics inherited from the mother, yet each has its own personality, interests, and abilities. Each picked a certain area or perhaps several techniques from long fist and developed them fully, in many cases pushing them to a very high level.

Long fist's well rounded training makes it an excellent choice to start out one's kung fu training. It gives its students a solid, basic foundation in kung fu—the building blocks necessary for the highest martial art levels. In contrast, there are major risks to beginning one's kung fu training in a specialized style. Assume that I have a strong attraction to bagua zhang. I am serious about my kung fu and spend years practicing bagua, only to find down the road that I have no future with this style. Instead, my talents lie in xing-i quan. What a waste! All my time and effort in bagua do not transfer over to this new style. I must begin all over.

Perhaps I am naturally gifted and have a bright kung fu future. I begin my training with a very specialized style. I practice hard and do very well. Later, if I wish to switch to another style, I will encounter big problems. When I practice my new style, the old techniques and flavor show through in all my movements. My progress is slow and the shift extremely difficult. In the end, my original style might well be the only one in which I can excel. Long fist won't present this kind of problem.

When a child starts practicing kung fu, it's almost impossible to know where his potential lies or how good he can be. In the field of music, for example, we may see that a child has great ability. But will he be a composer, conductor, a vocalist, master the cello? Will she become a professional, a talented amateur, a world-class performer? Most often, we first steer children to the piano and later on, support their interest in other instruments such as drums, or fields such as film score composition or musical analysis.

Long fist can somehow be compared to the piano: students may choose to specialize in it or not but no matter what they eventually do in music, it will help them a great deal. Long fist is an ideal path for fledgling kung fu students.

This is an era of specialization. Every field imaginable—medicine, computers, and so forth—is filled with specialists. Moreover, everyone is in such a great hurry. Therefore, many people today will automatically consider this lack a weakness in long fist. I myself don't agree—especially in view of modern times.

In the old days, a narrowed focus and speedy improvement were practical necessities. Not everyone who practiced martial arts had any love for them. Many had no real future in kung fu. It wasn't at all a question of talent, a burning interest, or a desire to achieve. You were a farmer who labored from dawn to dusk; there was a need for defense and you simply had to learn. You wanted to know just enough to effectively protect yourself and your village and the quicker your training progressed, the better. Social necessity, then, was one of the prime motivators in the development of specialized martial art styles.

Today the situation is altogether different. Given modern needs, the evenly balanced, comprehensive training for both body and mind is a shining treasure long fist offers to the contemporary person. This is an excellent style for us to practice and use throughout our entire lives. It is also an ideal way to begin our training, even if we later switch to other styles. If we switch, we won't have wasted our time, efforts, or hopes for our kung fu futures. And our experience with long fist will make us beneficiaries of the many valuable gifts it gives to ourselves personally and to our society.

End of Pt. 1

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

| [+/-] |

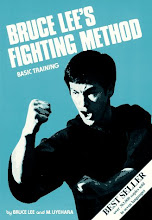

How to do the One Inch Punch! |

The concept of the One Inch Punch was introduced to Western Society by Bruce Lee. This technique, however, was not invented by Lee. Although he performed it flawlessly and showed the world how powerful the human form could be when issuing power, he never had a chance to learn the "Chum Kiu" of Wing Chun; therefore never getting the traditional stance of the form correct. However, Lee was still able to perfect his One Inch Punch, without needing a traditional stance. The concept behind the generation of power required is what he understood and applied perfectly, subsequently showing the entire world.

Fa Jin - The Base of Power

The literal meaning of Fa Jin is "Release of Engery". It is considered an "Internal" kind of power, as opposed to muscular strength. It has got a lot to do with the concept of "Chi". But that part of the story is not relevant here. It mostly has to do with staying relaxed and creating a fluid, whip-like motion that doesn’t "telegraph". It doesn’t rely on muscle power, but a kind of sudden, "explosive" force that the opponent can’t brace himself for. He has been thrown off-balance before he realized something happened. It leaves him quite shocked.

Now what is it? We all know what it feels like when we have to sneeze uncontrollably. Or when we are startled so bad that our hair in our necks stand on end and you feel this "electrical" tingling in our spine. Now that is natural Fa Jing! It has got something to do with that same uncontrollable force that’s unleashed while you’re sneezing. You can’t keep your eyes open, no matter how hard you try. That is how close I can can come to describing the essence of Fa Jing for you.

The "Internal Secret"

It is one of the major secrets of the "Internal" styles (like Bagua Zhang, Xinyi Quan, Yi Quan, Tai Chi Quan and Wing Chun). This is because it is their substitute for muscular strength. You can fill a library with the books that are published on the subject in Chinese alone. When one would study with a traditional "Internal" style teacher, one would learn all about the style for eleven years or so. If, after this period, one was considered trustworthy, it was only then that one was first learning about putting the power in your technique by applying Fa Jin!

There are many ways to generate Fa Jin. In Tai Chi Quan it is generated by shaking the waist violently. In Wing Chun it is derived from the ground. A smaller amount of Fa Jin can be generated from the wrist. But in Wing Chun the body is locked together in order to move like a single unit. The key here is relaxation. Without relaxation one can never generate Fa Jin

Attempt the Following:

Hold your hand horizontally, palm down, the fingers hanging down. Then make a SUDDEN punching-movement. The hand should snap into a fist by itself from the sudden speed. The arm and hand should stay relaxed at all times. Also when the hand is already clenched into a fist. Remember to NEVER tighten up! Relaxation and the suddenness of the movements are major ingredients in the effectiveness of Fa Jin. The opponent can’t prepare himself for it, can’t "brace himself", so to speak. That is why it is called "explosive power" and also "release power". It can be applied to free yourself from holds, to pull an opponent off balance, for pushing, palm strikes and punches of Bruce Lee’s famous "one inch punch" variety.

The Mechanics

The Wing Chun "Fatshaan Kuen" punching method is performed with the elbow down. Hence, we strike with a vertical fist. By tilting the fist slightly upward at the moment of impact, we "launch" the knuckles of the little and ring fingers, with a short "jolting" movement, into the target. Do not do this prior to actually having contacted the target. At the moment of impact, the arm should not be fully stretched. First stretch your arm after actual contact with the target is made and at the same time you "launch" your knuckles in an upward arc into it. At the same time, use your Wing Chun footwork to swivel. This gives you a few inches extra arm length. Practice until you can hit without stopping at the surface, going through it! The conventional way of hitting disperses the force over the surface of the target, while hitting INTO the target creates a shock-wave that damages the inside. It is of the utmost importance that you stay relaxed at all times. This doesn’t just enhance the speed of the punch, but it also prohibits "telegraphing". Most importantly it makes your arm into a whip-like structure through which the Fa Jin (internal explosive power) can travel freely. Explode into a sudden movement that goes from zero to ... within a fraction of a second.

The "One Inch Punch" Exercise

Face the punching bag squarely in a narrow horse stance, a Wing Chun basic stance. Measure the correct distance by placing your fist against the punching bag. If you can already stretch your arm to the full, your distance is too great. Your arm should be slightly bent. Hit the bag in a relaxed fashion, without reverting to muscle power. Switch in. At the same time stretch your arm and hit with the lower knuckles going upward and generate a short, shocking force coming from the ground. Try to hit into the target without pushing.

Application

In practical application, only use this technique when you are sure to hit the target. Once you are able to generate Fa Jin yourself by practicing exercises as described above you will begin to understand it more and you will find different ways to apply it. You can use the principle in palm strikes too, but be forewarned; this technique can be fatal. It can cause instant heart-failure and even rupture a person’s aorta.

Demonstration

Once you have learned the Fa Jin Punch, it is fun to demonstrate it like Bruce Lee did. Have someone holding a telephone book at the height of his solar plexus (breast bone). Now apply the Fa Jin Punch through the phone book, but never at full capacity!

Conclusion

The One Inch Punch SHOULD in fact be a "NO INCH PUNCH" ("One Inch is already too far away"). That is how what it was originally intended. Do not forget it is so much older than Bruce Lee. The technique is typical for the Nei jia (Internal) styles of Kung Fu like Tai Chi Quan and Wing Chun. There is a long version that throws someone off their feet or can be felt through a line of approximately eight people or so. There is also a higher level version, the Short- Fa Jin. The long version throws a person over an amazing distance, the short version drops him where he stands.

| [+/-] |

One Inch Punch Documentary |

This documentary covers the actual mechanics of the One Inch Punch.

| [+/-] |

Fa Jin (Expressed in Motion) |

Master Chen Xiao Wang of Chen Style Tai Chi executes Fa Jin movement with grace and power.

| [+/-] |

Fa Jin |

Fa Jin is the process of effectively issuing power through movement. This type of power is not the conventional type that we assume regular movements to possess. The type of strike that a boxer throws is, in relation to mass and speed, directly relative to the force that is subsequently received by the target. These types strikes are what make up most combat. An arm's length of distance, or even a bit farther depending on how far back one winds up, is the majority of the distance that will be covered by the object hitting the target. In terms of a strike from a fist, this is limited to how long the individual's arm is. With Fa Jin, the whole body is used in the completing the strike. In the case of a punch: there is a twisting motion that involves the whole body, starting from a properly rooted position, that progresses up the legs toward the torso and shoulders, which is ultimately released at end of fist. This results in a devastatingly powerful blow that contains the wound up energy of not just an arm's length of distance, but the entire length of one's body.

Monday, December 25, 2006

| [+/-] |

Not Always Hard, Not Always Soft |

Say the word "taiji", and most of us immediately imagine

qualities like soft, slow, tranquil, graceful, and flowing. So

when peoplesee performances of taiji quan which include

quick movements and power,they ask me "Is this right? Is

this really taiji?"To clear up the question, we must first clear

up our minds. To beginwith, taiji quan originally was a martial

art. To some people, it still is. Speed is a basic, fundamental

requirement of any martial art style. Martial artists must

issue power and power means hardness. Therefore any

taiji quan still practiced as a martial art will include quick

movements which issue power.

Change the focus from ancient Chinese martial art to universally

beneficial health exercise, and you now have a choice: a) slow, soft

movements only or, if physical condition and ability allow, b) a

combination of soft and hard, quick and slow. For a health-oriented

practice, either way is right, neither is wrong. Secondly, Chinese

kung fu is a very matured art and taiji quan a sophisticated style.

So most of the time taiji quan requires practitioners to move very

differently than in their daily lives at work and play. During the

early stages of training, therefore, we must wash away our old

habits of movement. Since old habits die hard, this becomes a

serious issue. Daily practice is an indispensable first step but it is

not enough . Practicing the entire form at a relaxed, slow pace

places us in a much better position to spot our problems and correct

our movements. Of course it's not impossible to do this at a quick

speed, but it is a lot more difficult.

The soft, relaxed pace of taiji quan also influences our internal

practice. When we execute a form with speed, we will quite naturally

--even subconsciously--try to put power into our movements. This

power, however, is of the raw, ordinary, daily-life, muscle strength

variety. It can increase only to a certain level. A punch of this type,

or instance, is pretty much as strong as our arm. It does not use

every part of the body to deliver its force. In other words, it's not

taiji quan power. That's why soft practice is so important. While slow

practice unveils our weaknesses, inconsistencies, and errors, soft

practice allows us to let go of our old ways of generating strength

and delivering power. And we must let go before we can move ahead.

As students, we should try to approach our taiji quan like babies. It

should seem like a mysterious, interesting new world to explore. Our

eyes must be fresh, our minds open, our bodies willing to learn a

totally new way to move. Our education starts anew in order to lead

us to the taiji quan way to issue power. This is why in the beginning

it's very important to execute the movements so softly--as if we

have no power at all.

Quite naturally, the majority of people in sports or movement arts

are at the beginning levels of skill.A much smaller group progresses

to the intermediate levels, even fewer are advanced, and only a tiny

percentage approach real mastery. So most of the taiji quan we see

in parks, community centers, and schools is at the elementary

levels. Perhaps this explains why everyone thinks taiji quan should

only be slow and soft. There are many components to a full tajiji

quan training program--for example, basics, forms, breath, forces,

posture, two-person sensitivity, and usage. As students advance to

higher levels, their training changes. New exercises may be

introduced, old ones modified,and the way students practice the

exercises must also progress. Changes in speed are introduced,

limited at first to a few movements in the form to give students a

taste. Later on, they learn to issue power in more and more of the

moves. Chen taiji quan has a famous first form, the lao jia

(Old Form), which contains some quick movements, punches, and

several different kicks--including a double jump kick. Its punches

even issue power. Chen style also has a lesser known second form

called Cannon Fist. As the name implies, the punches are delivered

with the speed, force, and intent of a fired cannon. Nowadays people

think of speed and power-issuing as trademarks of Chen style. Some

even use them as criteria to determine if a performance is Chen

or Yang. Not true! They are natural ingredients of the original art

of taiji quan.

| [+/-] |

Chen Style Tai Chi (Old Form) |

Performed by Chen Xiao Wang, Tai Chi master from the Chen Family.

| [+/-] |

Southern Praying Mantis Kung Fu (1956) |

The style shown is Jook Lum Southern Praying Mantis. Footage is from a Huang Fei-Hong movie made in Hong Kong (1956)

| [+/-] |

Jook Lum Praying Mantis |

Inside Kung Fu Magazine

A martial art is no less culture dependent than any of the other systems. In this case, it is about the praying mantis system of the people of a particular region of South China, and its practitioners in particular. Because I assume that most readers are familiar with the basic concepts of the Chinese martial arts so I shall briefly describe those which pertain to Jook Lum praying mantis. It is an internal system built around and constructed from the principles of chi gung. In its movements, it copies and stylistically embellishes the hand motions of the praying mantis while the footwork is patterned after the antics of the monkey.

Specifically, like the mantis, elbows are the critical fulcrum through which an opponent's attacks are controlled and countered. These are held tightly toward the centerline in front of the body, and through circular movements frequently combined with "sticking" hands, the opponent is quickly dispatched. The more advanced one becomes, the more subtle and elegant the movements, as in any other art form. The beginners' movements may be likened unto the pottery of the Ming, whereas those of the masters are not unlike the pottery of the Southern Sung.

Training begins with the horse stance; we all know the metaphors about houses and foundation. Ours is a tight stance with the toes pointed inward and the right foot approximately one-half step in front of the left. This permits rapid weight shifting and quick movement. When the student demonstrates some comfort with this (and believe me, it is not an easily acquired body posture), he begins to learn the hand techniques. All the while there are the chi gung breathing exercises which precede every lesson. From the day one begins this system until, presumably, the day of extinction one practices the chi gung. Within the rarefied circles of the highest levels of gung-fu, the grandmaster of this system, Lum Sang (often referred to as "Monkey") is famous for his chi gung. Those who have been involved with the martial arts for awhile know many wonderful stories that are associated with great masters and those that concern Lum Sang's chi gung are fabulous in every sense of the word. I might say that it is these stories that contribute to the palpable texture of a system: for gung-fu is not just temple boxing.

| [+/-] |

Wing Chun Grandmaster Yip Man (@ Age 79) |

Grandmaster Yip Man practicing Chum Kiu Form and Wooden Dummy. Yip Man is commonly recognized as the teacher of Bruce Lee. This was filmed 1 week before he passed away (due to throat cancer).

| [+/-] |

1 inch punch |

The infamous.

| [+/-] |

Seek the TRUTH in Combat |

Bruce Lee's Greatest Gift

to the Martial Arts -

How to Search for the Truth

by Raymond O'Dell

When you study the works of Bruce Lee, it becomes evident that you do not have to practice Jeet Kune Do to utilize his teachings. Lee taught us to "seek the truth in combat." While this is a major part of Jeet Kune Do, it is not a concept that is exclusive to it. It can be applied without regard to style or system. This concept and related lessons on how to search for the truth are probably Lee's greatest gift to the martial arts world. They have opened the door for countless traditional and eclectic martial artists to experience personal freedom and self-expression.

To martial artists, the phrase "seek the truth" can be a pretty abstract statement. I recently had a phone conversation with an old friend who is a second degree black belt in a traditional art. The topic of our conversation eventually came around to facing reality in combat. I asked my friend if he had ever read Bruce Lee's Tao of Jeet Kune Do (Ohara Publications Inc.). He stated that he had bought the book a long time ago but hadn't read it. Hearing this really hit home for me. I bought my first copy of the Tao in 1986 and tried to absorb it. I was also a second degree black belt in a traditional art. At the time, I did not understand all of what Lee was trying to get across, but I did understand enough of it to encourage me to dig deeper and seek out explanations for what I couldn't comprehend. What I came to realize was that the theme of the book revolves around one statement: Seek the truth in combat

Reality is the truth." With this in mind, your mission becomes one of seeking reality in combat. To make things easier to understand, you can substitute the word "reality" whenever you see the word "truth." Reality is a perception. What you perceive to be reality may not be exactly what your neighbour perceives to be reality. Lee took this into account when he said that your truth is not my truth and my truth is not your truth. We are all unique in how we perceive the world around us, and this includes combat or self-defense. Bruce Lee said that one person's reality in combat may not be another person's reality. For example, wing chun kung fu, which Lee learned from Yip Man, was an expression of what worked for the art's founder. The style might not work as well for all students, however.

"To see a thing [the truth] uncolored by one's own personal preferences and desires is to see it in its own pristine simplicity," Lee wrote. This means that you cannot look for reality in combat with preconceived notions or through the eyes of a martial artist or a boxer or a wrestler. To truly see what is taking place, you must look for what is real with an unfettered or unbiased mind. If you look with the eyes of a karate practitioner or a kung fu practitioner, you will see things only in terms of a karate practitioner or a kung fu practitioner. You will not see an unbiased picture.

Reality in combat is a broad topic whose meaning will change depending on the situation. In other words, more than one truth makes up combat. Each of these truths accounts for another term that Lee was fond of using: partial truth.

What is a partial truth? Many martial artists search for the truth (or reality) in a particular style or system. But, as Lee said, "You will not find the truth with blind devotion to a style or system, politics or obsession with tournament competition." If you try to search for the truth solely in one system or art, you will end up making yourself believe that the truth is there; or not seeing the truth, you will abandon the search altogether. Since you know that the truth will be different for each martial artist, what you will undoubtedly find is that each martial art contains things that have value to you or have a realistic function in terms of self-defense. What you have discovered is a partial truth within that style. When looking for reality in combat with an unbiased point of view, it is rare that you will find the whole truth in any one traditional martial art. That art, however, will almost always hold a partial truth. When you study a traditional or classical art, you are studying someone else's truth. You are studying what the founder of that art perceived to be his or her personal truth at the time the art was founded. An accumulation of these partial truths will make up the whole truth for you. You will learn, how ever, that the truth is in a constant state of change. The search never ends. Like your martial a rts training, the search is a journey and not a destination.

Bruce Lee's Path to the Truth

Tao of Jeet Kune Do, Bruce Lee's quintessential martial arts text, provides many clues that can help readers discover the truth in combat. The Tao teaches how Bruce Lee arrived at his personal truth, which he called Jeet Kune Do. The path he used is a clear and concise method that every martial artist can easily apply to his or her own search.

Seek the truth.

You have to consciously want to know the truth and look for it. Seek the reality of combat for yourself. Do not rely on what your instructor, past masters or other martial artists tell you is the truth. Do your own homework. You will not learn by copying your neighbor's homework. Take every opportunity to study what really takes place in an assault or self-defense situation, not just physically but mentally, too. What impact did fear, anxiety and anger have on the situation?

Become aware of the truth.

Know what you are looking for and do not be in denial when you discover it. Martial artists who have devoted years to training in a traditional system and have trained according to what they have been taught is the truth sometimes have difficulty accepting that they might have spent years studying a lie. Not only might they have studied a lie, but they might have spent years training according to that lie. Every martial art contains "partial truths" that are useful for the student of self-defense, but no one art contains them all, Bruce Lee said. It is the student's responsibility to discover which techniques and strategies work best for him.

One step in the method Bruce Lee described for finding your personal truth in combat involves "experiencing the truth." That translates into testing a technique you believe to be of value in a realistic full-contact environment.

The important thing is to not dwell on the lie. Be thankful that you have become aware of it and adjust your training to what you now know is real.

Perceive the truth.

Perception is everything in life and in the martial arts. Make your perceptions as total in nature as you can. Gather as many facts as possible on the subject or situation before forming a perception.

Experience the truth.

When you discover what you perceive to be a truth, put that truth to the test. In most cases, that means putting on the protective gear and going full contact in as realistic a scenario as you can come up with. This is an extremely important part of discovering the truth, one that many people fail to utilize. Lee was fond of saying that you cannot learn to swim without getting in the water. Likewise, you cannot learn to fight without fighting. How can you ever have any real confidence in your newfound truth if you haven't tested it in a full-contact situation? A word of caution about determining whether the truth you are experimenting with has any value: If that truth involves using a new technique with which you are not familiar, do not be too hasty to discount it if it fails. We all know that it takes time to master a new technique. The failure of the technique could be due to poor execution.

Master the truth.

Once you have perceived a truth, experienced it and found it to be true, master that truth. This involves drills and repetitive execution. As you should have done while experiencing that truth, practice it from all angles against many different attackers in as many scenarios as possible. Add the practice of this truth to your normal martial arts training regimen.

Forget the truth and the carrier of the truth.

What in the world did Lee mean by this? If the truth you learned was trapping skills, the carrier of that truth may have been the Chinese art of wing chun kung fu. Once you have developed your trapping skills, there is no longer a need to associate trapping with wing chun. Wing chun was merely a vehicle you used to get where you wanted to go. As mentioned earlier, wing chun as a whole is a truth that belonged to the founder of that system. One person's truth may be another person's limitation. By not being bound by this system, you avoid those limitations. You have effectively absorbed what is useful and rejected what is useless.

Repose in the nothing.

You cannot rest in the satisfaction of the truth that you have discovered because that truth will change with time. Long ago, empty-hand defense against a sword might have been a truth, but today it is highly unlikely that you will be attacked by someone wielding such a weapon. But a knife or baseball bat attack is quite conceivable. The truth of a sword attack has changed, or perhaps "evolved" is a more appropriate term. The fact is, the truth you discover today may be that the truth you learned yesterday is no longer true. "One man's truth in combat may not be valid for another person or another generation," said Bruce Lee.

Roadblocks to the Truth

You will be able to see the truth only after you have discovered the cause or causes of your own ignorance. This personal shortcoming sets up roadblocks that will keep you from finding the truth. The following is a list of some of the more common roadblocks that can keep you from seeing what is real. (If you sit down and think about it, you will probably be able to add many more.)

Loyalty to one martial art.

Lee wrote: "The man who is really serious with the urge to find out what the truth is has no style at all. He lives only in what is." Most styles claim to hold the entire truth of combat, but as I have already discussed, a style will hold the individual truth of the founder, not necessarily your truth.

Ethnocentrism, pride and ego.

The my-art-is-better-than-your-art attitude relates to loyalty to one style and will eventually hamper your ability to objectively look around you for reality. Pride is a double-edged sword. Being proud of your accomplishments is one thing, but too much pride can cloud your vision. It is also something you will have to swallow when the truth is eventually discovered. Ego is the result of too much pride. Its only purpose is to be bruised. When you are full of yourself, there is no more room for anything else.

A lackadaisical attitude.

If you are too lazy to do your own searching, you are not really serious about finding.

Prejudice.

Prejudice toward a race, creed, national origin, or martial art will keep you from experimenting with possible paths to the truth. As Lee said in Return of the Dragon, "It doesn't matter where it comes from; if it helps you look out for yourself in a fight, use it." By using Bruce Lee's path to the truth, and by recognizing and avoiding the roadblocks, you will not only be utilizing Jeet Kune Do, but you will also be on your way to finding great success in discovering your personal truth in combat. You will experience the ultimate in freedom and self-expression.

| [+/-] |

Kung Fu Grip |

by Grandmaster William Cheung

Every martial artist would like to know how and what made Bruce Lee such a devastating fighter. Even though a lot of people associated with Bruce Lee or many claimed to have trained him or trained with him, I can safely say that not many of them were privileged to his secret training method.

Bruce and I grew up together. We were friends since we were young boys. It was I who introduced Bruce Lee to Wing Chun School in the summer of 1954. In the old days, the master would never teach the new students. It was up to the senior students to pass on the Wing Chun lessons to Bruce. As I was his Kung Fu Senior of many years, I was instructed by Grandmaster Yip man to train him. By 1995, one year into his Wing Chun training, Bruce progressed very fast, and already became a threat to most of the Wing Chun seniors as the majority of them were armchair martial artists. They discovered that Bruce was not a full blooded Chinese because his mother was half German and half Chinese. The seniors got together and put pressure on Professor Yip Man and tried to get Bruce kicked out of the Wing Chun School. Because racism was widely practised in Martial Arts School in Hong Kong, the art was not allowed to be taught to foreigners. Professor Yip Man had no other choice but to bow to their pressure, but he told Bruce that he could train with me and Sihing Wong Shun Leung. But most of the time we trained together.

The first thing I showed Bruce was the Principles of being a good fighter:

1. The Heart

In a confrontation, one must desire to win;

When under pressure, one must maintain calm.

Famous quotation from Bruce Lee:

" No matter what you want to do, don't be nervous

(you should not let your muscles nor your mind be effected by nerves).

Just keep calm.

No illusion and no imagination,

but to apprehend the actual situation you are in and find a way to deal with it.

No excessive action is needed. Just keep your body and mind relaxed

to deal with the outside emergency."

2. The Eyes

The eyes should be able to pick up as much information as possible prior to and during engaging the physical struggle. Watching the elbows and the knees is essential to get the best result.

Also at no time, should the practitioner blink or turn his head because he would give away the most important instrument which supplies him the visual information of the current situation.

Extract from taped Bruce Lee conversation with Danny Lee (one of his students) in 1972:

Danny: Have you thought of Tai Chi as a form of self defence? Bruce: Well, if you were there ......... you would be so embarrassed, so it is not even a free brawl .......where a man who is capable of using his tools and who is very determined to be a savage legless attack whereas those SOBs are cowards. Turning their heads and swinging punches and after the second round they are out of breath. I mean they are really pathetic looking - very amateurish. I mean even a boxer because a boxer when they concentrate on two hands, regardless of how amateurish they are, they do their thing, whereas those guys haven't decided what the hell they are going to use. I mean before they contact each other they do all the fancy stances and all the fancy movements, but the minute they contact they don't know what the hell to do. I mean that's it. They fall on their arses and they .. and hold and grapple. I think the whole Hong Kong - they call it Gong Sao- Challenge Match in Hong Kong - can you imagine that, I mean even those guys see it that way. What do you think of the appreciation of people here? So what I'm hoping to do in film is raise the level."

3. Balance

This means the practitioner should be balanced at all times so that his mobility and stability are maximised. This also means that the practitioner must develop conditioning so that his legs do not give up under strenuous pressure.

Furthermore Bruce was very innovative. Back in the 50's, the Chinese Martial Artists were very conservative. They believed that weight training would slow down the practitioner's speed. But Bruce found a way to beat it. He would start his program with heavy weights and low repetitions first, then he reduced the weights and increased the repetitions. He continued to do that until his repetitions reached maximum and the speed of the exercise also increased. In this way he built muscles and developed power without losing speed.

One of the most important discoveries from his Wing Chun training was that Wing Chun teaches the practitioner to train with the individual muscle or group of muscles first, then co-ordinates the movement together by combining the muscles to make a collective movement in order to get the most out of the technique. Bruce had mastered this training.

The following is a subtle pose of a seemingly simple movement but it really does condition a few essential muscles on the arm in question. The other arm is pulled back, placed high but not resting on the body which is very tiring, enabling the brain to think about two arms at the same time. Hence the practitioner will be able to use both arms independently at the same time.

Bruce was also very much against high impact training such as the heavy bag kicking because he understood that the result from the high impact would only develop bulk muscles and they would slow down the practitioner's speed.

The following is the taped conversation ....Danny Lee 1972:

"Danny: Danny ( Inosanto) was excited yesterday.

Bruce: Yes, he was in my house the night before.

Danny: He didn't want us to do any more heavy bag kicking. He wanted us to just kick at something light.

Bruce: When you use your leg it is much better - to kick at the phone pad or whatever - watch out with the side kick on air kicking - not air kicking too much. If you snap it too much without contact at the end you can get hurt."

And later they discussed:

Danny: I think you have to pick a few diehard followers and say this is JKD.

Bruce: That's why I tell Dan (Inosanto) to be careful ... .........

Danny: So that's why - I've been working with Dan (Inosanto) a lot.

Bruce: I told him last time he's becoming very stylised. And it seems like his consciousness is really - something is bugging him.

Danny: I think its heavy bag kicking.

Bruce: Too much heavy bag kicking and too much body twisting has affected him.

Danny: Yes. The power and the momentum.

He's working out real hard.

I would like to conclude by saying that speed and power comes from relaxation and co-ordination which has everything to do with mind and body balance. From "The Bruce Lee Story" by Linda Lee and Tom Bleecker:

The following is Bruce's recollection of one of many training experiences with Professor Yip Man:

"About four years of hard training in the art of gung fu, I began to understand and felt the principle of gentleness - the art of neutralizing the effect of the opponent's effort and minimizing expenditure of one's energy. All these must be done in calmness and without striving. It sounded simple, but in actual application it was difficult. The moment I engaged in combat with an opponent, my mind was completely perturbed and unstable. Especially after a series of exchanging blows and kicks, all my theory of gentleness was gone. My only one thought left was somehow or another I must beat him and win.

My instructor Professor Yip Man, head of the Wing Chun School, would come up to me and say, "Loong (Bruce's Chinese name), relax and calm your mind. Forget about yourself and follow the opponent's movement. Let your mind, the basic reality, do the counter-movement without any interfering deliberation. Above all, learn the art of detachment."

That was it! I must relax. However, right there I had already done something contradictory, against my will. That was when I said I must relax, the demand for effort in "must" was already inconsistent with the effortless in "relax". When my acute self-consciousness grew to what the psychologists called "double-blind" type, my instructor would again approach me and say, "Loong, preserve yourself by following the natural bends of things and don't interfere. Remember never to assert yourself against nature: never be in frontal opposition to any problem, but control it by swinging with it. Don't practice this week. Go home and think about it."